By Anne Chesky Smith

In the midst of the Great Depression, Marcus Lafayette Martin moved his family east to Swannanoa, North Carolina, where he was able to find work in one of the nation’s largest blanket mills, Beacon Manufacturing. Why, when so many others were losing their jobs, was he able to find steady work?

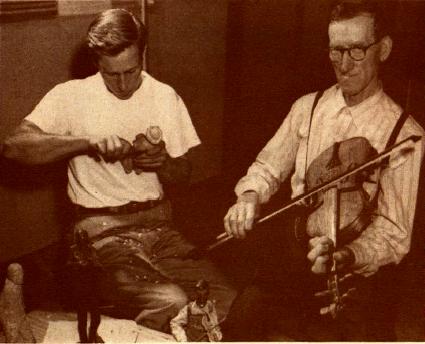

Beacon’s owner, Charles D. Owen, did his best to make sure his workers were happy—providing housing, shopping, and entertainment for his employees and their families. In a time before television, where few workers could afford to go to the movies or own a radio, music and sporting events were the major forms of entertainment. So, according to local legend, when Owen heard Marcus fiddle—it was said Marcus could “fiddle a possum out of a tree, fiddle all the bugs off a sweet potato vine, and fiddle the heart right out of your throat”—Owen offered him a job on the spot and a place for him and his boys to live in his mill town.

Born in 1881 in the Aquone community of Macon County, North Carolina, Marcus was the grandson of a Cherokee Indian Chief and a Scotch-Irish woman and as such became tied to the musical traditions of western North Carolina. Though he would be best remembered for his masterful fiddling—many of his recordings are currently housed in the Library of Congress – he was also a traditional ballad singer and an accomplished banjo, harmonica, and mountain dulcimer player.

His father, Nathaniel “Rowan” Martin, taught Marcus most of his repertoire and technique, and though Rowan himself never found acclaim as a musician, Marcus remembered years after his father’s death that he “could play the sweetest you ever heard.”

Marcus began playing publicly in his youth, often fiddling tunes at square dances around Macon and Cherokee counties unaccompanied. As a young adult, Marcus worked with his father on the farm, but soon found work in his community’s dry goods store and later became the postmaster in the community of Rhodo.

Marcus married Callie Holloway Martin, a “good five-string banjo picker” herself, and had six children – five boys and one girl. After a short stint working in a laundry in Gastonia, Marcus separated from Callie and moved with four of his boys to Swannanoa. It was here, in the Swannanoa valley of western North Carolina, that Marcus became well known as a musician.

When Bascom Lamar Lunsford began organizing the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in Asheville in 1928, Marcus soon became a favorite of Lunsford’s and opened the festival for many years with the traditional tune, “Grey Eagle.” He continued to travel and play with Lunsford throughout his life, performing as far away Renfro Valley, Kentucky and Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

During interviews, Marcus claimed that he “didn’t know a thing about music.” He never remembered learning to play. He just said, “Don’t ask me how it come to me. I don’t know for sure. I guess it was talent, if you would call it that. Just come naturally. All my ancestors were musicians, see, and I guess I took it from them.”

Marcus knew dozens of songs by heart and held the title of “Champion Fiddler” at the 1949 North Carolina State Fair in Raleigh. When at the 1950 State Fair no one had the courage to play against him, the rumor began to circulate that he would no longer compete, so that others could have their chance.

Though his music career was taking off, Marcus still spent most of his time working at the Beacon mill. In his spare time, he made fiddles to sell. He had learned to carve from his father—who “was gifted with wood” according to Marcus’ son Wade, but who had only used his skills for practical purposes, fashioning plow handles and other farming tools. Carving as an art form came later for the Martin men, when their factory jobs provided them with cash money and free time.

Marcus made fiddles and mountain dulcimers, always spending the extra time to carve the scroll at the end of each instrument. He carved reluctantly, only making about a dozen dulcimers and carving figurines only when commissioned. Several of his sons, however, were quick to learn the art of carving from their father and develop it further.

One son, Edsel, using only his pocket knife, would carve native western North Carolina birds that he saw in his yard, whittle hounds dogs, and shape the likenesses of mountain people. The Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. even asked him to carve a pair of each of North Carolina bird species for permanent display. The dulcimers Edsel made had their scrolls shaped into human faces, dog heads, and flowers. The songs he played, he learned from his father. Musician and friend Billy Edd Wheeler remembered Edsel’s playing. “He grew up with these songs, heard them played by his daddy as often as he heard the birds sing, and as naturally.”

Another son, Wade “Gob” was also a prolific carver. He explained that his carvings were not measured or planned, they were simply “felt.” He said of his carving, “I guess somewhere back, my forbearers probably had something to do with that. I believe there are hand-me-down talents.” Though Wade acknowledged his father’s role in developing his carving talents, he also told another story to explain his inspiration.

One day he was out looking for wood to carve when a tiny door opened in a nearby tree and “out stepped a little old bearded mountaineer man that was about the size of a large ear of corn. In his hands he held a tiny fiddle and a fiddle bow.”

The man gave Wade a magical knife that he promised would “promote and emulate [his] carving ability and speed to a point of uniqueness.” The tiny man began to play “Amazing Grace” on his fiddle and then other “wee folk” came out of the tree and began to sing. At the end of the song, the fiddler asked all the “wee folk” to gather around Wade so that he could have a lasting impression of them. When Wade returned home, he began to carve. Soon he had produced scale models of the fiddler along with banjo, guitar, bass, and dulcimer players. When all five figures were finished they came to life and began to play the “good old mountain music” just like his father taught him to play.

Marcus and his boys have all passed away, but their handmade instruments and carvings can still be found scattered around western North Carolina in museums, archives, libraries, and private homes.

This family history was researched using materials in the archives of the Swannanoa Valley Museum, located at 223 West State Street in Black Mountain. A version of this article was published in Vol. 29 No. 2 2014 edition of Now & Then: The Appalachian Magazine.