By Anne Chesky Smith

(first published February 2018 Black Mountain News)

This is how it was, then, for Mary Stepp Burnette Hayden.

“She used to tell me how she would have to outsmart a catamount that picked up her scent as she walked home through the mountains at night, carrying a chunk of fresh pork, her payment for a new delivery,” Mary O. Burnette said last week of Hayden, her grandmother and a midwife and herbalist renowned in the Valley.

“She would hear this animal squeal and … she would start pulling off garments. Pull off a bonnet, throw it down and she’d hear that animal stop long enough to tear that up and she’s still running. Then she’d pull off something else, maybe a vest, and then an apron, and then undergarments or even stockings if she needed to and had the time, so she could make it home.”

Often descended from enslaved midwives, midwives in the latter 19th and early 20th centuries were typically African-American women who learned the trade from their mothers. Mary Stepp Burnette Hayden of Black Mountain was no exception.

Born in January 1858 to Hanah Stepp (c. 1832–Nov. 6, 1897) on the Joe Stepp farm in Black Mountain, Mary learned to deliver and care for babies from her mother, who had served as a midwife from a very young age, having been sold to the Stepps from a plantation in Alabama when she was 13.

Though Mary O. Burnette never met Hanah Stepp, she heard stories about her. “My mother said (she) had very black skin, but not African black,” Burnette said. “And she had a strange dialect. My grandmother said she was part Native American.”

According to the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, in the early to mid-1800s, when Hanah Stepp would have been practicing, slave ownership included directing treatment for sick or injured slaves. African-American beliefs about the causes of illnesses, however, often differed greatly from the beliefs of white slaveholders and their physicians, who called for treatments that were typically much harsher than the natural remedies favored by enslaved people.

Though Mary Stepp Burnette Hayden told Burnette little about being enslaved, Burnette recalled one story that stood out. “She remembered when slavery was abolished. She told me that a man came on a horse and stood before her mother’s cabin door and read to them the Emancipation Proclamation. She was 5 years old. It would have been in January of 1863. It was one of the most wonderful things she told me.”

Mary Hayden and her mother most likely stayed in Black Mountain at the Stepp farm until the end of the Civil War in 1865, and perhaps in Black Mountain for a time afterwards, so that Mary could learn to read and write at a local school for former slaves. Hanah’s skills were not place-dependent, and she was able to help sustain the family – Mary Hayden and her two sisters, Margaret and Easter – as a midwife. The family eventually moved to Polk County.

Mary married her first husband, Squire Jones Burnette, by the time she was 18. They had many children, but only two survived to adulthood – Mary O. Burnette’s father, Garland Alfred Andrew Burnette, and her Aunt Margaret. Mary Stepp Burnette and Squire divorced, and her second marriage to Andy Hayden was short-lived. In the 1910s, Mary Stepp Burnette Hayden moved back to Black Mountain, following her son, who had purchased a small farm in town.

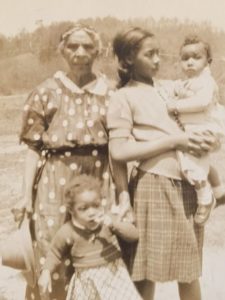

Hayden would live in Black Mountain for the remainder of her life and continue to support herself as a midwife and herbalist. Mary O. Burnette, who was delivered by Hayden along with her six siblings, remembered of her grandmother, “She was small. Tiny woman. Maybe 100 pounds. Very small foot, but very hearty. Tough. And a very straight nose, small mouth. Intense, stern eyes. Bushy eyebrows.

“She had long straight hair that hung below her waist. Her hair was twisted into two ropes and those ropes were twisted tight at the back of her neck. I used to stand behind her chair and comb and brush her hair, and I’d have to keep backing up because her hair was so long.”

One day, Hayden went out to pick blackberries. As she was picking through the brambles a long, black thing fell down over her shoulder. Startled, she jumped away from the what she thought was a black snake. Upon closer inspection, she declared, tossing her head back and clapping her hands, “Gentlemen, it was just a braid of my hair!”

“That was Granny’s manner of speaking when she wanted to make a point,” Burnette said.

Hayden dressed modestly, in skirts down to her ankles; rarely, if ever, buying new clothing. “She made her long white aprons by hand,” Burnette remembered. “She would sew a pocket that went all the way to the hem because that’s how she carried things. I never remember her having a purse, she would drop things in that apron pocket so she would have things handy, particularly her snuff … She would reach down and pull the hem up so she could get her hand all the way down to the bottom of that pocket.”

Inez Daugherty, a Black Mountain resident and civic leader who passed away in 2007 at age 95, remembered only two midwives who served Black Mountain – her aunt, Annie Daugherty and Mary Hayden.

Born in the High Top Colony community of Black Mountain in 1888, Daugherty delivered many of the babies born in Black Mountain, Katherine Daugherty Debrow told a local filmmaker in 2001. Hayden may have delivered the rest.

“If there were any whites, I don’t know about them,” Daugherty told an interviewer for an oral history archived at the Swannanoa Valley Museum & History Center.

Though there were a multitude of white doctors across the Valley, Mary Hayden and Annie Daugherty treated white patients as well as black ones. “It didn’t matter whether the family was black, white, willing to pay or even if they had not paid for the previous delivery, Granny would gather her supplies and ‘light out,’” Mary O. Burnette, a Black Mountain resident who is Hayden’s granddaughter, said two weeks ago. “She knew they didn’t have money.”

Daugherty and Hayden made house calls, regardless of the time of day or weather, for folks who couldn’t afford a doctor or didn’t have the time to make it to one.

The Rev. Eugene Byrd, a white Black Mountain teacher, coach and Baptist minister who passed away in 2015 at 99, talked about his birth to an interviewer in an oral history stored at the Swannanoa Valley Museum & History Center. “I was delivered by Aunt Mary Hayden, who of course was a person who did that sort of thing, ‘cause the doctor was a little bit slow a-getting there.” The Byrd family land was adjacent to the Garland Burnette family land near Allen Mountain.

“Fortunately, Granny (Mary Hayden), well into her 80s, was present when my sister delivered her second child,” Burnette said. “She looked at the child after the doctor had left, and the child had no features. Granny was familiar with the caul and slipped her thumb under the veil and pulled it off.

“(She) was still ‘catching babies’ long after her great-grands came along. And expectant mothers would send for her after the law required a medical doctor to be in attendance for the birth.”

In the 1920s, state governments began to require midwives, who had traditionally been trained informally by a relative, to get permission slips from doctors to practice. The state required midwives have their homes inspected for cleanliness and have their moral character assessed. These new regulations disproportionately affected African-American and low-income families.

So, Hayden approached the county to receive sterile supplies for her work. She may have been the first African-American woman to be registered with the Buncombe County Health Department as a midwife. For a while she lived in a small, three-room house off Cragmont Road owned by the Nix family.

“Granny would deliver their babies,” Mary Burnette said, “so they let her live there until one of their children needed the house … At that house was the only time I ever remember her having a doctor. She treated herself.”

Historically, because enslaved people in North Carolina often had little choice about many facets of their lives, they tried to maintain their own medical traditions. Often concealing illnesses from slaveholders, they sought treatment from other slaves – or treated themselves – using herbs cultivated in their gardens, plants gathered in the wild, and the knowledge of their family and friends. Many remedies were also necessary to treat injuries obtained during work, including whipping wounds.

Still, by the early 1900s, “healthcare (for African Americans in the Valley) was available only through healers and midwives,” said Inez Daugherty. “We could not go to Mission or St. Joseph’s” hospitals in Asheville.

In 1927, French Broad Hospital was established in Asheville for black people, Daugherty noted. But it was 15 miles away in Asheville, and few people in the community had cars. Transportation was not the only problem. “We had no money for doctor and hospital bills,” Burnette said. And information about, and money for, insurance was limited.

Years later, in the 1940s, another hospital opened in Asheville to serve black patients. Though transportation options into Asheville and earnings had improved over the last two decades, the service at that facility was poor and the hospital soon closed, according to Burnette.

Because of the midwives’ extensive knowledge of herbal and home remedies, people through the early and mid-20th century relied on Hayden and Daugherty not only for delivering babies but also for treating a variety of ailments.

“My first cousin, she had a baby. And it had jaundice,” Inez Daugherty said. “And Aunt Mary Hayden went down to see, and she told her what to get and what to do, and it cured Daniel.”

The government, in addition to regulating midwifery in the 1920s (and fully outlawing lay-midwifery in the 1970s), also began to ban the use of herbs and poultices, greatly curtailing treatments for patients unable to afford hospital care.

“(Mary Hayden) could cure just about anything with herbs,” descendant Pearl Lynch said in a Black Mountain News story published in 2015. “She knew so much about them, and when she died (on Jan. 6, 1956), all that knowledge was lost.”

Mary Burnette is sure that some of the herbal remedies she remembers were passed down from Mary Hayden, and perhaps came from even further back. “There was Jerusalem Oak,” Burnette said, “and you could find it in our fields. A lot of kids had worms back then, and you’d make it into tea with sugar and it would kill worms.”

Jerusalem Oak, also known as wormseed, was harvested commercially through the mid-20th century for use in medicines to treat hookworms in both humans and animals. Though lower cost alternatives have been found, it is still used for fragrance in lotions, perfumes, and soaps.

“But the most common tea was ground ivy, a little vine with a fan-shaped, scalloped leaf and a little purple flower,” Burnette said. “Make that into a tea and you can drink that to help you sleep at night.” Besides use as a sleep aid, ground ivy has also been shown to be useful in treating coughs, bronchitis, arthritis, stomach problems, kidney stones and mild lung problems. It is also currently being studied for use in preventing leukemia, hepatitis, cancer and HIV.

Today, there is no licensing or certification for herbalists in North Carolina – or in any state – meaning that anyone can use, dispense, or recommend herbs. However, without an doctor’s degree, herbalists are not allowed to diagnose disease nor tell people that their treatments will prevent, treat, or cure illness. Still, many of these remedies passed down from generation to generation are in use today.

“My sister, who used to follow Granny around through the fields and knew a lot more than I did,” Burnette said, “she said Granny told her that every herb has three kinds – one is a healer, one is a just a weed, and the other is a poison. I thought that was marvelous. A positive, a neutral, and a negative.”