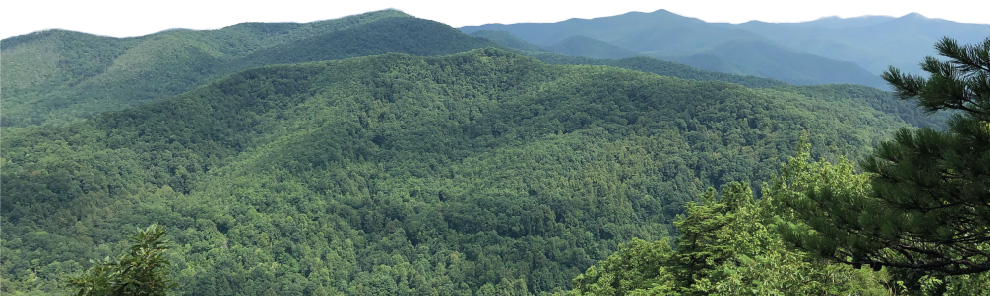

FIRST SETTLER WEST OF THE BLUE RIDGE: SAMUEL DAVIDSON (1736-c1784)

Samuel, Mary, Ruth, and Liza–a small family and the woman they enslaved–

were the first non-Native settlers in the Valley

“At the close of the Revolutionary War the territory which now comprises NC west of the Blue Ridge was claimed by the Cherokee as tribal hunting grounds. Other Indians, and sometimes even white men, hunted occasionally [here] without arousing violent antagonism….A settlement on the land they viewed in quite another light…”

– Foster A. Sondley, 1913

Many of our valley’s most well-known stories have been passed down from generation to generation. As stories pass from person to person, details can bend and twist, leaving historians scrambling to find out the “truth.” The story told about the earliest settlement of our valley by non-Native people is one such case.

Though we believe the first non-Native settlers ventured across the Blue Ridge and built a cabin near Christian Creek in the Swannanoa Valley in the 1780s, it wasn’t until nearly a century later that we find the first written account of their brief stay.

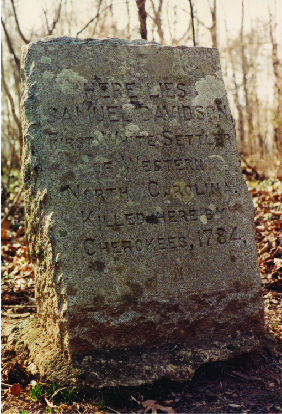

“Our grand uncle, Samuel Davidson…had worked his horse all day, and turned him out to grass at night. Next morning he walked out to get his horse, and had not been long gone until his wife [Mary] heard the sound of a rifle shot: and, taking the alarm, she snatched up her infant daughter, Ruth, and leaving the path, she made her way across the Blue Ridge about twenty miles to a fort [Davidson’s Fort, now Old Fort] on its eastern slope. A negro woman left about the same time, and made her way back to the fort along the path.”

– Robert B. Davidson, 1870

Left: Illustration of Samuel Davidson by Douglas Gorseline in Wilma Dykeman’s The French Broad.

“A party, mostly relatives, set out to avenge him in death. They found his scalped body on the mountain…. They gave it proper burial and followed the nearby trail until they encountered a hunting party they supposed to be the murderers. After a skirmish, the Indians fled, leaving one or two dead behind.”

-Wilma Dykeman

The French Broad

Wilma Dykeman (1955) and Foster A. Sondley (1913) are amongst several authors who have recounted this story. In one of the more compelling versions, Johnny Baxter, a descendent of the “negro woman,” told of Liza’s heroism in dragging the surviving members of the family that enslaved her from the cabin and down the mountain to safety. In her honor, her name – Liza – has been bestowed upon a female family member every generation.

Right: A contemporary reproduction of Davidson’s Fort (Old Fort). Courtesy of Davidson’s Fort Historic Park.

Bill Alexander, a descendant of the Davidson family, recounted this story in the oral tradition of his family in an interview in 2012. Listen to his narrative below.

Whatever actually happened to the valley’s first non-Native settlers, this story exemplifies the interactions between European, Native, and African peoples in the late 18th century in the region: white settlers were pushing westward at the expense of the Native populations, all while building their growing economy on the backs of enslaved people.