Joara and Fort San Juan: A Summarized Look at the Juan Pardo Expeditions

This year, the Swannanoa Valley Museum is hosting the traveling exhibit 2020 – Unearthing Our Forgotten Past: Fort San Juan. Learn more about the fascinating history of the Joara and the Juan Pardo expeditions below.

1. Life in the Carolinas 500 Years Ago

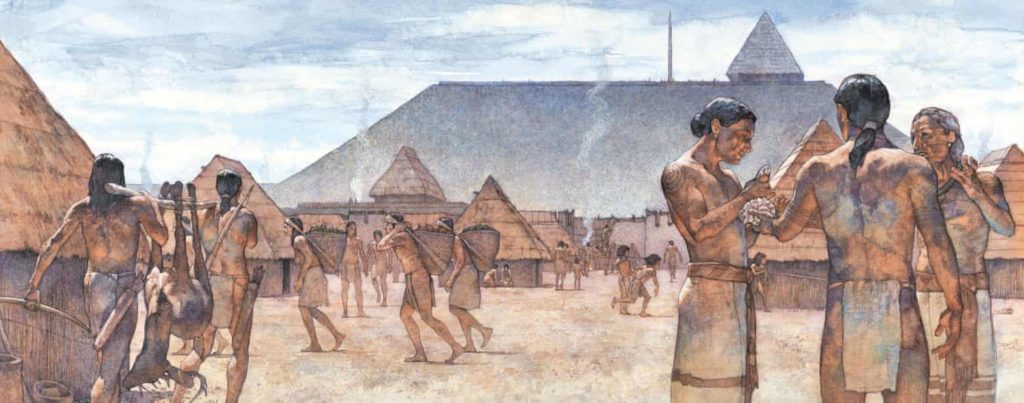

Above: An illustration of the Mississippian town of Cahokia, credit Alamy.

What did communities in North Carolina look like 500 years ago? Continuing with our Tuesday Posts on the Joara Exhibit, today we’re setting the stage for what happened in the 1560s in the Upper Piedmont- near present-day Morganton- between the Juan Pardo conquistador expedition and the people of Joara. Read all the way to the end to find out one of the Swannanoa Valley’s many connections to this history!

Archaeological research in the last few decades has revealed that in the 16th century- and at least 100 years prior- the upper Piedmont was a highly populated area, dotted with large regional centers and smaller outlying villages and farmsteads. During this time, Upper Piedmont peoples practiced what would now be considered a mix of Mississippian and Woodland cultural lifeways. Many peoples depended on agricultural crops such as maize, beans, and squash, and supplemented their crops with foraging, hunting, and fishing. Some communities lived in large towns with defensive palisades, open plazas and mounds, while others occupied small towns and farmsteads dispersed along rivers and other waterways.

Portions of the Catawba River Valley were divided into polities, or regional chiefdoms. Joara, situated just 8 miles north of present-day Morganton in Burke County, was the capital of one such polity. Evidence suggests that Joara was, in fact, the most important political center in the region in the mid-16th century.

These communities in the Catawba River Valley were highly connected across the Southeast through a network of trails used for trade. These trade networks extended to the coastal plain of the Carolinas, and west into Southern Appalachia. Early Cherokee peoples traded with the chiefdoms of the Upper Catawba, and in fact one of the important trade routes connecting these communities went right through the Swannanoa Valley! Folklorist James Mooney notes that the word Swannanoa comes from the name for this trail- the Sualinnunahi- meaning the Suwali (or “Joara” trail).

These communities are whom the conquistadors Hernando de Soto and later, Juan Pardo, interacted with- often with devastating consequences for Native peoples- at various points in the 16th century. More on these men in future posts.

2. Joara: The Burgeoning Town Encountered by de Soto and Juan Pardo

Above: A portion of a Spanish Map, made in 1584, of Southeastern Native towns and chiefdoms, by Geronimo Chaves. “Xuala” or Joara, is visible in the upper center.

When Juan Pardo arrived in Joara (or “Xuala”) with his men in 1566, he found a regional chiefdom in its ascendance, with a powerful leader at its helm. Located about 8 miles north of present-day Morganton, NC, Joara was one of the largest towns in the Catawba River valley, and one of the few to have a mound. Joara was the capital of a polity, or chiefdom, led by a regional leader or “mico”- the Joara Mico. In their travels through the Southeast, Pardo and his men encountered many local leaders of towns- called “oratas”- but only 3 micos, indicating the high status of such men and women. Joara Mico held authority over several other towns along the upper Catawba and its tributaries, and during Spanish occupation of Joara, he was able to embroil the Spaniards in his own political aims by convincing them to make war on regional rivals in southern Appalachian towns in modern-day Virginia and Tennessee. This would result in Pardo traveling through the Swannanoa Valley to attempt to rescue some of his men- more on this in future posts!

Joara seemed to fare better from the effects of Spanish colonization than many chiefdoms in the Southeast. Hernando de Soto travelled through Joara in 1540- several decades before Pardo and his men would arrive. But as far as is known, de Soto did not have a lasting influence on the town. Decades later, after 18 months of occupation by Pardo’s men, the locals would rise up and kill all of Fort San Juan’s soldiers, excepting one escapee. Evidence suggests that Joara continued to thrive into the 17th century. Today, both Cheraw and Catawba peoples of the Carolinas understand themselves to be descended from the Joarans.

3. St. Augustine & Santa Elena: How the Spanish came to launch a campaign into the Southeastern Interior.

What do St. Augustine, Florida, Parris Island in South Carolina, and Morganton, NC all have in common? They were all sites of Spanish colonization in the 1560s. Spanning a distance of 400 miles as the crow flies, all three of these locations hosted Spanish forts and settlements, all of which were built by the Spanish within two years of each other.

What do St. Augustine, Florida, Parris Island in South Carolina, and Morganton, NC all have in common? They were all sites of Spanish colonization in the 1560s. Spanning a distance of 400 miles as the crow flies, all three of these locations hosted Spanish forts and settlements, all of which were built by the Spanish within two years of each other.

By the mid-16th century Hapsburg Spain- ruled by Phillip II- was at the peak of its power. Spain’s dominion extended to every continent then known by Europeans. In fact, the phrase, “The Sun Never Sets on the British Empire” was first utilized to describe the Spanish Empire during the reign of Charles I, Philip II’s father. By the 1560s, Spain had already sponsored several expeditions into the Americas, including those of Christopher Columbus, Hernán Cortés, Francisco Pizarro, and Hernando de Soto. In 1562, French attempts at settlement in the Southeast would trigger a series of events that would eventually lead to the founding of St. Augustine, Santa Elena, and Fort San Juan.

Between 1562 and 1564, French Huguenots founded two settlements on the Southeast coast- Charlesfort, at Parris Island, South Carolina, and later Fort Caroline, about 40 miles north of present-day St. Augustine, in Florida. The Spanish, who had claimed these territories, responded by sending conquistador Pedro Menéndez de Avilés to drive out the French. In September of 1565, Menéndez and his troops arrived in Florida and slaughtered or captured all the inhabitants of Fort Caroline. Menéndez founded St. Augustine that same month, and then in 1566 sailed north to modern-day Parris Island, building a new fort- Fort San Felipe- and settlement- Santa Elena- directly on top of the ruins of Charlesfort.

Santa Elena was established as the first colonial capital of Spanish Florida, and when Philip II learned of these developments, he ordered reinforcements for Menéndez’ colony. In July 1566, Captain Juan Pardo, a member of the king’s private guard, arrived at Santa Elena with 250 men and they soon began to fortify the settlement. However, the Santa Elena colony was not prepared to feed such a large company of men for very long- so Menéndez ordered Pardo to prepare half his army for an expedition into the interior regions that lay beyond the Atlantic coast. In the coming months, Pardo’s expedition would found Fort San Juan.

Above photo: An 18th century portrait of Menéndez

4. Pardo’s First Expedition and the Founding of Fort San Juan

When Juan Pardo arrived at Santa Elena (on modern-day Parris Island, SC) in 1566 with 250 men, colonial governor Pedro Menéndez de Avilés knew that he would not be able to feed the new army of men. He ordered Pardo to take half his men into the interior of La Florida, today the Carolinas. Pardo was tasked with exploring the area, claiming the lands for Spain, pacifying the Native residents, and forging an overland route from Santa Elena to the Spanish silver mines in Zacatecas, Mexico. This last task was based on the misunderstanding that the Appalachian Mountains and the Rocky Mountains, both known to the Spanish by this time, were the same mountain range. Thus, the distance between Santa Elena and Mexico was thought to be much shorter than in reality.

Pardo left Santa Elena with 125 men in December 1566. Over the next few weeks, his entrada army would enter several towns and villages across modern-day South and North Carolina, amongst them Guiomae, Canos (also known as Cofetazque and Cofitachequi) and Ysa (“Ysa” is a variant of “Esaw,” the name applied to one of the core peoples of the Catawba Nation in the early eighteenth century). At most of the towns that Pardo entered, he told the cacique and his subjects to build a house for the expedition and fill it with maize.

Two or three days north of Ysa, Pardo entered the Province of Joara, located along the tributary of the upper Catawba River in the Appalachian foothills. Pardo stayed at Joara for 15 days. As the capital of a chiefdom with a powerful leader- the Joara Mico- Joara made an impression on Pardo. He ordered the construction of Fort San Juan, and bestowed the name of “Cuenca” on both the town of Joara and the settlement he founded. From Joara, Pardo could see snow on the Appalachian mountains, and so he halted his westward push in favor of conducting further explorations of the Piedmont.

Pardo marched northeast from the upper Catawba Valley, spending several days at the towns of Guaquiri and Quinahaqui before leaving the Catawba River. In the central Yadkin River Valley he and his men spent several weeks at Guatari (later called “Wateree” by the English), near modern-day Salisbury. At Guatari, Pardo left the company cleric, Father Sebastian Montero to establish the earliest mission in the interior of North America. Pardo and his remaining army went back to the Catawba-Wateree Valley, passed through several villages, stopped again at Canos, and arrived in Santa Elena on March 7, 1567.

Six months later, Pardo would depart again for a second expedition into the interior. In the meantime, Hernando Moyano, the sergeant at Fort San Juan, would aid the Joara Mico in devastating attacks against Native towns in Appalachia. More on Moyanos’ foray in next week’s installment.

Photo: “Building Fort San Juan de Joara at the Berry Site (1566-1568).” John Klausmeyer/ University of Michigan, Museum of Anthropological Archaeology

5. Moyano’s Foray into Southern Appalachia

In early 1567, when Captain Juan Pardo departed the newly founded Fort San Juan, he left Sergeant Hernando Moyano in command. After further explorations of the Piedmont, Pardo made his way with the remainder of his men back to Santa Elena. But at Fort San Juan, nestled in the thriving town of Joara, the town’s leader- the Joara Mico- had plans for his new guests. The Joara Mico convinced Moyano and his soldiers to accompany a Joaran expedition on attacks of several Native towns in Southern Appalachia. These attacks may have had to do with a tribute dispute, but the Mico’s motivations are unclear. What narratives we do have about these forays come chiefly from a Spanish account written in 1567.

Thirty days after Pardo made his return to Santa Elena, Moyano sent news claiming he had defeated “a cacique…named Chisca.” He wrote that he had killed more than a thousand Chisca Indians and burned fifty huts (the former number is probably exaggerated). Soon after this attack, another cacique from Southern Appalachia sent threats to Joara and Moyano, and another expedition was launched to attack the cacique’s town. Moyano and 19 of his soldiers, accompanied by a party of warriors from Joara, marched for 4 days across the mountains where they found their enemies enclosed by a high wooden wall. They breached the palisade, burned the town and reportedly killed 1500 Indians (these numbers are, again, very likely exaggerated).

Domingo de Leon, a translator who participated in Pardo’ second expedition, recalled that the towns attacked by Moyano and the Joarans were called “Maniatique” and “Guapere.” Maniatique was located along the North Fork of the Holston River near present-day Saltville, Virginia. Guapere- the second village attacked- was probably located along the upper Nolichucky or Watauga River in present-day east Tennessee.

After the attack at Guapere, Moyano remained in East Tennessee. He and his men arrived at the town of Chiaha, situated near the confluence of the French Broad and either the Nolichucky or the Pigeon River The people of Chiaha gave Moyano’s men a warm reception, and soon after Moyano departed for a town led by the chief Olamico. Arriving in Olamico’s town, Moyano built a small fort, and waited for Pardo to begin his second expedition. When Pardo would return to San Juan in late 1567, he would be forced to launch an expedition to aid Moyano, and this expedition would lead him through the Swannanoa Valley. Next week: Pardo’s Second Expedition

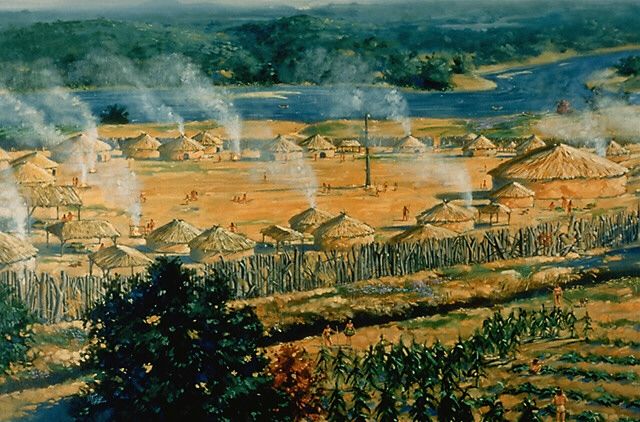

Above photo: A view of a Mississippian era town. Photo credit siue.edu.

6. Pardo’s Second Expedition

On September 1st, 1567, Pardo left Santa Elena for a second time at the command of Menendez, taking 130 soldiers with him. Pardo’s party traveled towards Joara, and on their way they were hosted by several towns including Canos, Tagaa, Gueca, Aracuchi, Otari, Quinahaqui and Gauquiri. Most of these towns had built storehouses filled with maize for the Spanish, as had been Pardo’s command on his first expedition through the region. At Canos and Quinahaqui, Pardo met with several caciques from Ylasi, Vehidi, Ysa, Cataba, and Yuchiri- the latter of whom might have represented a group of Yuchi-speaking peoples. This is also the first documentation of the term “Catapa” cognate of “Catawba” that would come to represent most Carolina Piedmont peoples after 1720.

On September 24th, Pardo arrived at Joara and learned that Moyano “was gone from the fort…and that the Indians had him under siege.” Pardo departed for Chiaha immediately.

His company marched for 3 days to a town called Tocae, “a place which is over the top of the ridge [of mountains]” according to the expedition’s scribe. Some anthropologists suggest that Pardo and his men crossed into the Blue Ridge Mountains at the Swannanoa Gap and that Tocae was located near the modern city of Asheville. After meeting with Cherokee leaders at the town of Cauchi, Pardo reached Olamica, town of the Chiaha, on October 7th. Moyano’s men were hard pressed, but safe, and the united party left three days later. However, they soon were forced to turn back again when they learned of an intended ambush, and the Spanish returned to Olamica. There Pardo established Fort San Pedro. When it was safe for the expedition to leave again, Pardo left 27 men at the fort. Traveling back toward Joara, Pardo also established Fort San Pablo at the town of Cauchi, leaving it with 11 men. On November 6th, Pardo’s reduced company returned to Joara and rested for twenty days, during which time Pardo received a large number of regional cacique leaders.

Before leaving, Pardo manned Fort San Juan with 30 soldiers and outfitted the fort with a broad range of supplies. Pardo had been displeased with Moyano’s behavior, and so new leadership was given to Alberto Escudero de Villamar, who was not only made commander of Fort San Juan, but was given authority over all the forts between Chiaha and Santa Elena.

Pardo and his company left Joara on November 24th, staying at towns they had previously visited, including Ysa and Guatari. At the latter town, the residing mico was a woman. DeSoto, who had traveled through the Southeast in 1540, had also met with a female mico- remembered as the “Lady of Cofitacheque”- at Canos. This means that two out of the three micos who received Pardo and Soto in the Carolinas were women.

In Guatari, the Spanish established Fort Santiago. After visiting several more towns and establishing a strong house at the coastal town of Orista, Pardo returned to Santa Elena with less than a dozen men on March 2, 1568. At this point in time, Pardo likely felt proud of the many new forts he had established, and perhaps even felt assured that Spain’s influence could grow stronger in the region. But by May 1568, news reached Santa Elena that Indians had attacked all of Spain’s interior forts and that all had been destroyed.

Above photo: An interpretation of Pardo meeting with leaders at Joara.

7. Why the Forts Fell

By May 1568, news reached Santa Elena that all of Spain’s interior forts- from Fort San Pedro in modern day East Tennessee to Fort San Juan and Fort Santiago in the Piedmont- had fallen. All six forts had been attacked by Indians and destroyed. It is unclear if these attacks were coordinated and simultaneous, or if they occurred in stages. There was ostensibly one Spanish survivor from these attacks, Juan Martin de Badajoz, who, possibly through the negotiations of his Indian wife Teresa Martin, was able to leave Fort San Juan before his comrades were killed.

Though we will never have a complete picture of what triggered these attacks, there are two likely predominant factors: The Spaniards’ demands for food and their impropriety with Indian women. Concerning food, the conquistadors and the Natives almost certainly had contradicting expectations about the presentation of food from the beginning of the Spaniards’ occupations of native towns. The Spaniards viewed the natives as their subjects, and as such, they owed the men continued sustenance as tax or tribute. But from the Indians’ perspective, food was presented as part of ongoing exchange of goods or other services, and the Spanish brought few trade goods with them on Pardo’s expeditions. The Spaniards’ ongoing demands for food would have been insensible to the Indians, who felt they owed the Spanish nothing.

Concerning sexual interactions- The Spanish soldiers certainly had relationships with Indian women, which likely varied in their power dynamics. Moyano’s men took Indian women during their expeditions into Virginia and East Tennessee, and some of the women taken from the Southeastern interior became the wives of Spanish soldiers, such as Teresa Martin. Some of these interactions may have been against Pardo’s wishes. Before Pardo left several men at Guatari, he commanded “that no one should dare bring any woman into the fort at night and that he should not depart from the command under pain of being severely punished.” However, Teresa Martin later testified that Pardo’s men left in the interior waited “three or four moons” for Pardo to return. When he failed to do so, they began to commit improprieties with native women, angering their men.

A third possible factor that could have motivated Indians to attack the forts was mistreatment and abuse by Spanish soldiers. A Jesuit priest, Juan Rogel, observed that many Spanish soldiers felt free to mistreat Natives even when in close proximity to disapproving commanding officers.

Regardless, the destruction of Fort San Juan and the five other forts was a significant instance of indigenous people successfully resisting European colonization. The extermination of the Spanish from much of their interior occupation precipitated the shrinking of Spanish claims across the Southeast. Santa Elena was abandoned in 1587, after which the boundaries of the Spanish empire were largely restricted to St. Augustine and the boundaries of present-day Florida. No other Europeans would travel so far into the southern interior until the last quarter of the 17th century.

Photo: The remnants of For San Juan, destroyed by fire, are being uncovered by archaeological teams today. Photo credit Robin Beck.

8. The Iron in the Post Hole

In 2007 at the Berry dig site, archaeologists discovered a piece of iron jack plate armor at the bottom of a posthole that had supported the entryway into a Spanish colonial kitchen near Fort San Juan in the town of Joara. In this colonial kitchen, Indian women would have prepared meals for the soldiers of Fort San Juan during most of their occupation of the town. Some of these women were residents of Joara, while others were Chisca, enslaved by Pardo’s men during Moyano’s forays into modern-day East Tennessee. The placement of the iron in the post hole at the Berry Site indicates that Spanish soldiers feared the perceived magical powers of these women, especially in their role as cooks and providers of food.

In many European folk magic traditions, it is understood that certain objects, placed at the boundaries of a home or other structure, can help to protect the residents and their possessions from harm. These objects, placed over mantles, buried under doorways, in one’s yard or ensconced in a wall, can ward off curses or malignant actions by witches or other magic users. These objects were often everyday materials such as shoes, hats, iron, nails, and bottles filled with pins and needles. It was not unusual for animals and animal parts to also be used to ward away magic. Cats could be buried in walls, and horse skulls might be buried in gardens (These practices are not confined to European traditions- they are also common in African and African-American practices).

Since these objects and animals have long been a part of domestic life, it can be challenging to identify recovered artifacts as magical tools. However, the unusual location of the jack plate armor fragment and its positioning in the hole- tightly wedged between the posthole cut and the upright post- indicates that it could have been intentionally placed by a soldier to be used to ward off magic. This armor may have been intended to prevent the women’s use of sorcery on the food they were preparing for the soldiers. In other words, the armor might have been used to prevent magic from leaving the kitchen once food was taken out and served to the Spanish.

But why was the making of food considered a potential threat by the Spanish soldiers? During the 16th century, Spanish perceptions of female witchcraft included the idea that women could enchant the food they served men, and the consumption of this food by men enacted the woman’s intended curse or enchantment. Spanish men believed that marginalized women, including widows, single women- and in the case of colonial America- Indian women were the most likely to use magic.

The placement of the jack plate armor is indicative of the profound sense of vulnerability felt by Pardo’s men. Isolated in an unknown country, and attempting to dominate those around them, the Spanish perceived threat and siege in many elements of their everyday lives- including the food served to them by the women they enslaved. And of course, the Spaniard’s fears of Native aggression or retribution would indeed become a reality when the people of Joara burned down Fort San Juan and killed its soldiers by May of 1568.

Photo: Jack plate armor consisted of pieces of metal or iron sewed into cloth to form a protective vest. The sizes of the iron used could vary. Photo credit Antiques Trade Gazette.

8. The Spaniards’ Search for Quartz Crystals

Quartz crystals can be found in outcrops throughout western North Carolina. The Spanish considered quartz crystals to be a source of wealth, though not as valuable as gold or silver, and Spanish documents tell us that the soldiers living at Joara traveled into the mountains to search and mine for “crystals” and gold. Spanish colonists across the Southeast and the Caribbean spoke of “Los Diamantes,” a fabled mountain of diamonds in the interior, and the men at Fort San Juan may have fantasized about finding just such a place. Archaeologists found a quartz crystal next to an iron scale in House 5 at the excavation site at Joara. The quartz may have been brought to Fort San Juan by soldiers in 1567 or 1568.

Quartz crystals can be found in outcrops throughout western North Carolina. The Spanish considered quartz crystals to be a source of wealth, though not as valuable as gold or silver, and Spanish documents tell us that the soldiers living at Joara traveled into the mountains to search and mine for “crystals” and gold. Spanish colonists across the Southeast and the Caribbean spoke of “Los Diamantes,” a fabled mountain of diamonds in the interior, and the men at Fort San Juan may have fantasized about finding just such a place. Archaeologists found a quartz crystal next to an iron scale in House 5 at the excavation site at Joara. The quartz may have been brought to Fort San Juan by soldiers in 1567 or 1568.

9. Pisgah Pottery at Joara- A link to the Appalachian Mountains

Most of the American Indian pottery found at the Berry dig site near Morganton is from the Burke Pottery series. This pottery is often characterized by its distinctive types of decoration- complicated stamp designs made with a carved wooden paddle and incised designs that are carved into wet clay with a pointed object (see photos below). However, a different kind of pottery style has been found in the area occupied by the Spanish at Joara. A large round pit near House 5 in the Spanish compound contained fragments of Pisgah pottery. Pisgah pottery is made in the mountains of North Carolina and eastern Tennessee, but it’s very rare to find it in the Catawba River Valley at sites such as Joara.

Why was this pottery in the compound? There are several possibilities. The people of Joara could have traded for the pots or goods inside the pots. The pots could have been brought by Indians who traveled from the mountains to meet Pardo. The pots could also have been made by women from the mountains who were visiting or living in the compound. During the Spaniards’ excursion into modern-day southwest Virginia and east Tennessee, they kidnapped and enslaved several women and brought them back to Cuenca. It could have been that these women, so far from home, made Pisgah pottery in the styles familiar to them while they lived in the Spanish compound. It is unknown what happened to many of these women. At least one of them, Luisa Mendez- kidnapped from Maniatique near present-day Saltville, VA- married Spanish soldier Juan de Ribas. The two eventually left the interior when the Spanish abandoned the Carolinas and by 1600 they were in St. Augustine, Florida. But in the early days of Luisa’s imprisonment she may have made Pisgah style pottery, and perhaps this pottery helped her remember the community and family she had lost.

Photos: Pisgah jar rim from Garden Creek mound no. 1 in Haywood Co., NC courtesy of Ancientnc.org, a Burke phase jar fragment with carinated rim and a Burke Phase complicated stamp jar fragment, both from the Berry Site at Joara, courtesy of the Warren Wilson College Archaeology Department.

10. Mississippian Homes in the 16th Century

What did Mississippian homes look like?

The tipi of Plains Indian traditions is the stereotypical representation of all Native building styles, when in fact Native building styles have always been diverse and evolving. So what did Mississippian homes look like in the southeast when the Spanish arrived in the 16th century? Mississippian houses in the Piedmont and the mountains of North Carolina were square. The homes were often constructed of wooden wall posts and a central roof support. The walls were often made from waddle and daub and the roof would be covered in thatch or bark. The homes would have a central hearth for light, heat and cooking. In other parts of the Southeast during the same period, Native builders often preferred round houses constructed from saplings bent to meet in the middle, then covered with bark, mats or thatch to create the roof and walls. The square house featured in the image is a reconstruction of the houses found at Joara and is part of the Living History Village at Catawba Meadows near Morganton. Photo courtesy of https://www.morgantonnc.gov/.