Images from NC State Archives, Western Regional Office

Images from NC State Archives, Western Regional Office

by Anne Chesky Smith

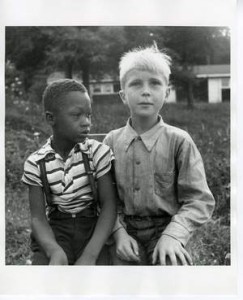

In the early- to mid-1900s, the Swannanoa Valley, like most places in the South, was segregated. African Americans could not attend Black Mountain’s movie theater or eat inside restaurants.

Local legend has it that one of the first integrated spaces in the Valley was Roseland Gardens, an African American juke joint run by Horace Rutherford in the Brookside community – now the Flat Creek Road area.

Though Rutherford ran the establishment to cater to African Americans who could not patronize local establishments, he also had a few Caucasian customers as well. For the most part, however, full integration did not occur in Black Mountain until well into the 1960s.

And integration was not easy, even for one of the most progressive places in the Valley – Black Mountain College. The college, founded in 1933 at Blue Ridge Assembly, discussed the subject of race throughout its 24-year history, beginning in its very first year.

In 1933, a father of one of the students, who was a professor at Yale University, was traveling the South with several of his graduate students – one of whom was black. He asked the college if they could stop in for a few days.

Immediately the community began an intense discussion of whether the student should be housed on campus with every else, or (as was customary in Black Mountain at the time) whether he should be put up with a local African American family.

Though many at the college were in favor of allowing the student to stay at the school, others felt that allowing even temporary integration might be the last straw for the surrounding community, which already viewed Black Mountain College as a haven for free love and Communism. In the end, the student was housed with a local family.

The issue would be broached several times throughout the 1930s, but did not come to a true head until 1944 when the students voted two to one to admit African American students as full members of the college community, which was now located at Lake Eden.

The faculty, however, were more cautious and less idealistic – and though almost no one felt that they should exclude quality students due to the color of their skin, half of the faculty wanted to (again) err on the side of caution. They reasoned that Black Mountain College had not been set up to challenge segregation and that doing so could potentially cause the demise of the school.

At first many of the opposing faculty cited a North Carolina law that did not allow segregation in schools, but when it turned out that the law did not exist, an abundance of other reasons were found.

There was fear of violence against college personnel, arson against the college property, boycott of Black Mountain students and faculty by local businesses, increased ill-favor of local citizens, and a smaller likelihood of being accredited which would discourage veterans studying on the GI Bill (a big source of funding for the school at the time) from attending.

The integration supporters, however, had their own ideas of what desegregation would mean for the college. They listed the following in support of their goal: the satisfaction of living up to our ideals, greater respect from our students, intellectual and artistic contribution of black students, greater financial support from approving individuals, and an already approved $2,000 from the Rosenwald Fund.

In the end, the school made a cautious compromise and agreed to allow a well-qualified, graduate-level African American woman – Alma Stone Williams – to attend the 1944 summer program at the college. Williams would later say of the college, “It is important to recognize Black Mountain College’s role in the history of integration in America… It was willing to take a risk to bring me into the community…they gave me the freedom to learn beside them and to be myself.”

There was little backlash from the community, and only one student left the college in light of the decision to cautiously integrate, so, in 1945, the college invited Carol Brice and Roland Hayes to teach at the summer institute, and enrolled Sylvesta Martin as Black Mountain College’s first full-time student.

In 1947, eight years before Chief Justice Earl Warren would declare “separate educational facilities…inherently unequal” and order the desegregation of schools, Black Mountain College was fully integrated.

Despite this progressive attitude, however, few African American students would choose to attend Black Mountain College, perhaps one of the many factors that contributed to low enrollment and indebtedness in the late 40s and early 50s that would eventually led to the school to close its doors in 1957.

Despite its short history, Black Mountain College remains an inspiration for progressive education and art around the world.